Sadhus — My encounters with the holy men of India. On my first trips to India in the early 1970s, everything was unfamiliar to me at first. The traffic, the smells, the food, the language, the way people dressed and behaved—the whole explosion of impressions, colors, gestures, and sounds. But that was precisely what attracted me. I had read Hermann Hesse's “Siddhartha” and wanted to delve deeper into this (at least in my view) completely different world.

1973: My First Encounter with the Holy Men.

I found the sadhus – the holy men (there are also women, but only a few) who practiced extreme asceticism – particularly strange and therefore all the more fascinating. I encountered them for the first time in 1973 in Haridwar and Rishikesh, pilgrimage sites at the foot of the Himalayas. Naked and rubbed with ashes, they sat in front of small fires called duni. Their hair often reached the ground and was matted, their gazes often distant, as if they were in another world. Believers bowed before them, touched their feet, and gave them a few rupees for a blessing.

Ash on the skin, eternity in the eyes.

It was sometimes eerie when the sadhus looked directly at you. I often encountered piercing glances that triggered all kinds of feelings in me—sometimes I felt respect or admiration, sometimes compassion, but sometimes also aversion or even fear. The latter was especially true when they demanded money intensely. Today I know that there are also charlatans. “Real” sadhus never beg directly and are not aggressive. I am all the more relieved that I did not let my first encounters with false ascetics deter me, but instead continued to follow my curiosity.

Because I had burning questions: What preoccupied these holy men? Why did they renounce the world? How did they feel? What kind of freedom did they experience? And was their quest for moksha, salvation, really worth all the hardship and deprivation?

I would have loved to talk to them. But we were separated not only by cultural barriers, but also by language barriers. And so, at first, I mainly observed from a distance as they wandered through markets, often scantily clad, with their staffs and begging bowls, sitting on the sides of roads or in front of shrines.

In 2010, when I had the good fortune to visit the world's largest religious festi-val, which is traditionally attended by countless wandering monks, I finally got closer to them.

Kumbh Mela, a celebration of faith and a meeting ground for ascetics.

I visited the camp of the Juna Akhada Sadhus. This is one of the most im-portant and oldest Hindu monastic orders. Known for its strict discipline and rigorous spiritual practices, I simply approached one of the sadhus there. And although he could only speak a few words of English, we managed to com-municate with each other. I felt welcome with that sadhu. He and his fire pit became my anchor point.

A special bond emerges, requiring

almost no words at all.

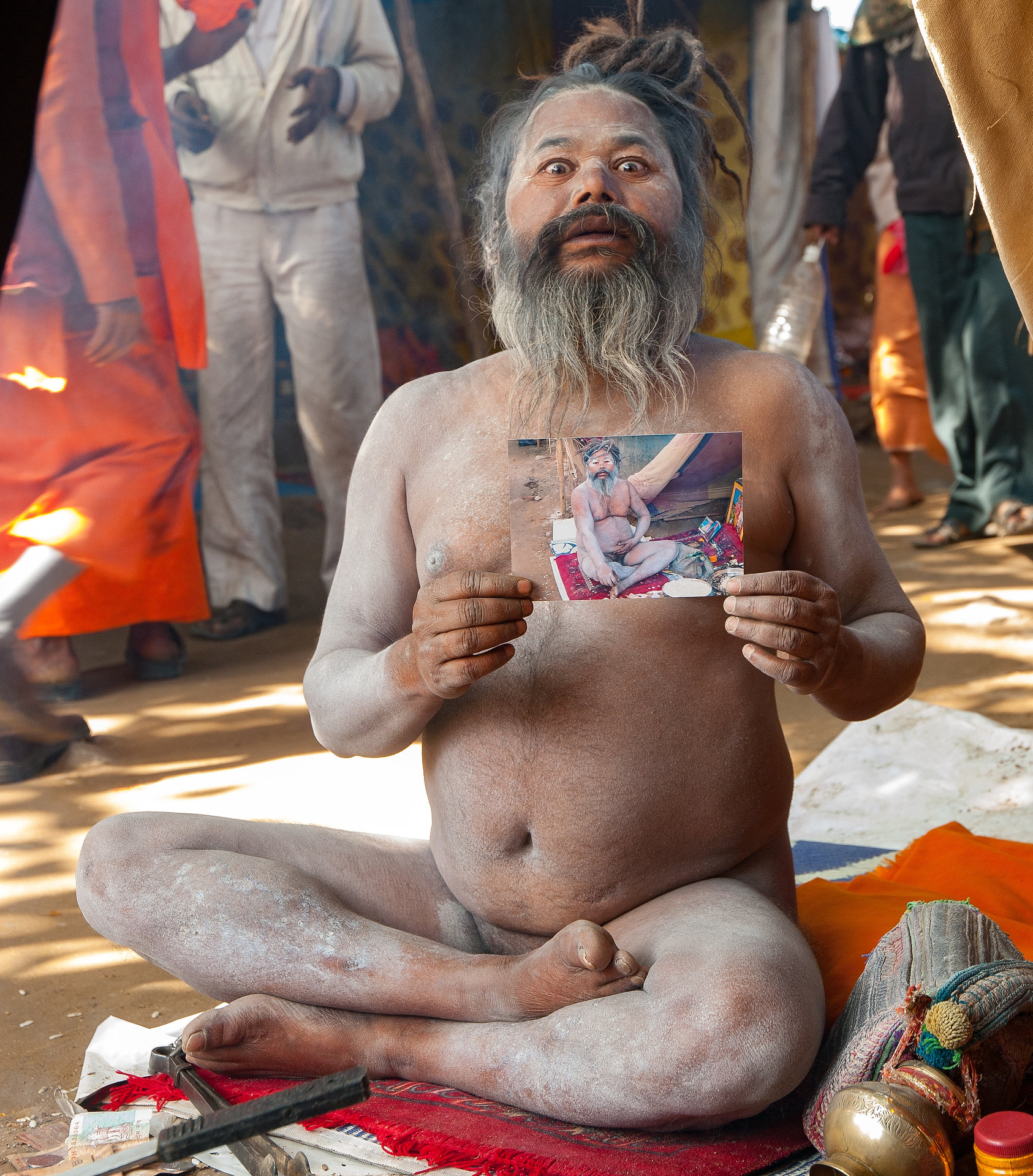

From here, I set out with my camera and wandered through the busy streets and the gigantic bustle of the festival, taking numerous portraits of various sadhus. I had the films developed overnight and presented the holy men with prints of their portraits the next day. They were delighted, and so I made more and more contacts.

A photographic mission on the sacred river — my images open doors.

One day, however, when I visited my sadhu friend at his fire pit and greeted him as usual, he did not respond. Instead, he handed me a note. It said that he had taken a vow and would not speak for “six.” I asked, “Six days?” He shook his head. He shook his head at six weeks or six months as well. Only when I said six years did he nod. Fortunately, he was still able to communicate with me in writing or by hand signals.

A vow of silence and the torment of self-control.

Soon after, I learned more from other sadhus about the tasks they imposed on themselves to prove their devotion. Some showed me their “yoga tricks” – or what they understood to be such. The lotus position and extreme asana positions were still the most harmless of these.

A naked baba, as sadhus are also called, wrapped a metal skewer around his pe-nis. But that wasn't all: he also turned it around several times and hung a 20-kilogram stone block from it. Another sadhu demonstrated his self-control in a similar way – with two people standing on the left and right of the skewer.

I also came across a so-called “Khareshwari” or “Standing Baba.” These are sa-dhus who never lie down or sit down. This sadhu had been standing continuous-ly for four years. When I asked him how he could stand it, he told me that only the first few days, weeks, and months had been terrible. His body had now be-come accustomed to it. He offered me to hold his legs. I did so – and was shocked. There were no soft spots left on his thighs. They seemed to be made of stone. The consumption of cannabis probably also helped him. Some sadhus consider it a means of recognizing God or being closer to him.

The serene power of the Sadhvi—the sacred women.

At some point, to my amazement, I discovered a camp where there were only female sadhus. This is because you encounter them much less frequently in everyday life. There were no fires burning in front of their tents, nor was there the smell of hashish. Their presence consisted mainly of friendly reserve.

The appearance of the famous guru “Pilot Baba” was completely different. Before becoming a sadhu, he was a lieutenant colonel in the air force. Apparently, a near-death experience had led him to the spiritual path. However, something from his old life seemed to have remained: he took part in the Sadhu Akharas procession with a large entourage.

Leaving the earthly world behind.

There are many different kinds of sadhus, and there are certainly many different paths to spiritual development. I have read that there are about 400,000 sadhus in India. They are mainly found in the north, in holy places such as Varanasi, Haridwar Nashik, Ayodhya, Mathura, Rishikesh, Badrinath, Vrindavan, Rameshwaram, Pushkar, and Puri. With a total population of 1.4 billion Indians, 400,000 is not a large number.

The all-too-human side of the journey toward Nirvana.

A dignified sadhu from the Juna Akhara, adorned with countless chains, initially ignored my attempts to approach him – even though he was very photogenic. He remained aloof. So I ignored him too and occupied myself with the ascetics sitting nearby. It was like a game between us.

In the days that followed, he finally began to seek my attention, first tentatively and then more insistently. It was an interesting experience. I had the feeling that he was deliberately playing a role to win me over. I thought: In a way, we all play roles in the end – whether we are sadhus or not.

Once I even witnessed a fake sadhu being exposed in a camp. An angry crowd handed him over to the police – and beat him up first. He may have been a fugitive criminal. It sometimes happens that crooks pretend to be ascetics in order to lay low for a while. And of course, there are also simply cunning beggars who dress up as mendicant monks. After all, giving donations to sadhus is part of everyday life in India. So it's no wonder that among them there are also people who are, in the truest sense of the word, more “hypocritical” than holy.

In fact, the more I got to know the sadhus and the more personal connections I built up with them, the more an interesting thought dawned on me: Was I dealing with completely normal people after all?

Some practiced special forms of devotion, and some seemed quite sublime. Others, however, repeatedly displayed all-too-human traits, including jealousy, selfishness, greed, and lust. Did I ever meet a sadhu who had already attained nirvana? Good question, I don't know!

But none of that detracts from my fascination with them. They no longer neces-sarily have an aura of specialness about them for me. But I meet them with joy and respect. I greet them with “Om Namo Narayan” (“The soul in me greets the soul in you”) and can say one thing with certainty: they are no longer strangers to me.

continue

traveling ...

My Hippie Trail: From Kassel through Kabul to the Roof of the World. The trip to India was the great longing of my generation. In 1972, at the age of 22, I gathered all my courage, gave up my apartment, packed my backpack, and boarded the train—off on the legendary Hippie Trail toward the Himalayas.

Helmut Haase

Photography & Stories

Alle Texte und Fotos sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Wenn Sie an der Nutzung bestimmter Inhalte interessiert sind, nehme ich gerne Ihre Anfrage entgegen.

© Helmut Haase 1975 – 2025